We learned quite a bit about emerald shiners in the three years since our research began. As we process and analyze our data, we would like to share what we have learned about this important native prey species with you.

Check this page periodically to see our results and upcoming publications!

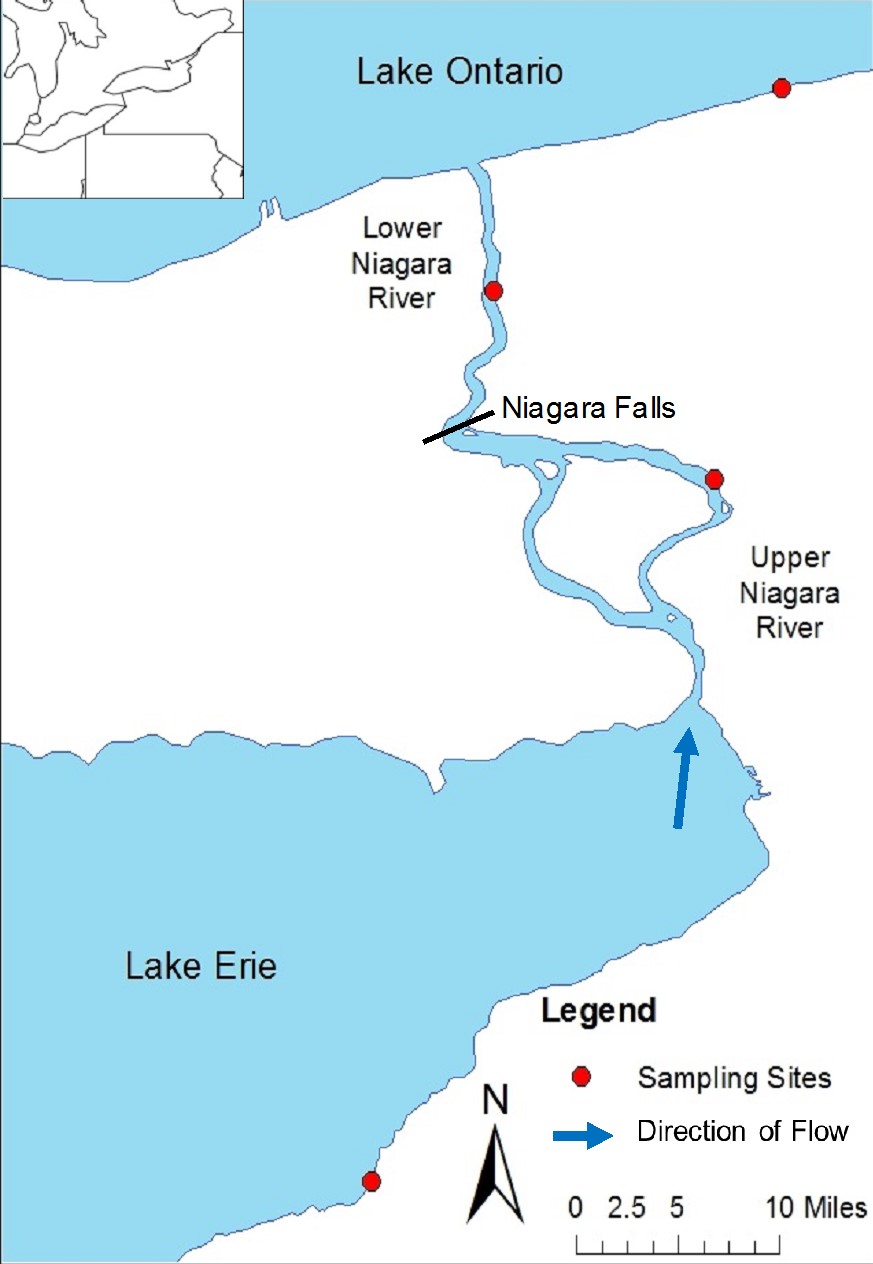

This research project aimed to use geometric morphometric techniques to determine if there are differences in body shape between emerald shiners collected from the upper and lower Niagara River, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario. Differences in habitat (e.g., flow and prey regimes) have been shown to drive adaptive divergence in fish. For instance, fish inhabiting faster flowing water generally exhibit more streamlined bodies than their lake counterparts. Individual emerald shiners were photographed for this project and their body shape was digitized. Statistical analyses were conducted using various computer programs that compare body shape data.

The results of this study demonstrated that, on average, emerald shiners from Lake Erie and the Niagara River had a dramatically different body shape than individuals from Lake Ontario. Specifically, Lake Erie and Niagara River individuals had deeper, more robust bodies, which was an unexpected result. The findings also suggested that factors other than flow regime may have been responsible for the divergence in body shape.

This data will be paired with population genetic data from these same four populations to better understand levels of gene flow across emerald shiners in this system. Increasing our knowledge of connectivity between these emerald shiners may have management implications. Future studies should investigate the influence that predator communities may have on the morphological divergence between emerald shiner populations.

Emerald shiners with two different body shapes: one with a deep, robust body (top) and a streamlined body shape (bottom). Please note these photos are not at exactly the same scale.

Map of four sampling locations from Lake Erie, upper Niagara River, lower Niagara River, and Lake Ontario.

Map of four sampling locations from Lake Erie, upper Niagara River, lower Niagara River, and Lake Ontario.

The objective of this study was to examine the seasonal and age-class differences of emerald shiner diet using fatty acid and stable isotope analysis. The same approach was used to study the role the emerald shiner played in the diet of top resident predators in the upper Niagara River. While stomach content analyses can be used as a snapshot of what a fish had most recently consumed, fatty acid and stable isotope analysis better inform diet preferences reflective of long term feeding habits.

We used direct methylation for the fatty acids analysis of both the emerald shiner and its hypothesized predators. The direct methylation technique uses both methylating and extracting solutions to remove all fatty acids from the homogenized fish tissue. Twenty emerald shiners and ten predators (smallmouth bass, largemouth bass and white bass) were used per age group and season.

The results suggested there is a temporal shift in the diet consumed by the emerald shiner from early June to mid-October in both 2014 and 2015. These data also suggest that diet changes with emerald shiner age-class (young of the year, age 1 or age 2 fish). Furthermore, the fatty acid profiles for the three predators are roughly 75-85% similar to that of the emerald shiner. The 75-85% similarity observed indicates that although emerald shiners are not eaten exclusively, they are a major component of their diet.

The emerald shiner has never been studied before in the Niagara River and seldom studied in other parts of the Great Lakes. This research helps to provide a better understanding of what diet type the emerald shiner consumes at different points in its life cycle, as well as different times of the year. Additionally, it provides strong supporting evidence that the emerald shiner is an important prey source for many valued game fish. As a result, it is crucial that they be maintained and protected within the upper Niagara River.

Two important prey items (chironomid larvae [top left] and Daphnia spp. [top right]) recovered from the stomachs of emerald shiners. Important resident fish predators (bottom) that were studied to determine how important emerald shiners are in their diet. Smallmouth bass (top two), largemouth bass (bottom) and white bass (not pictured).

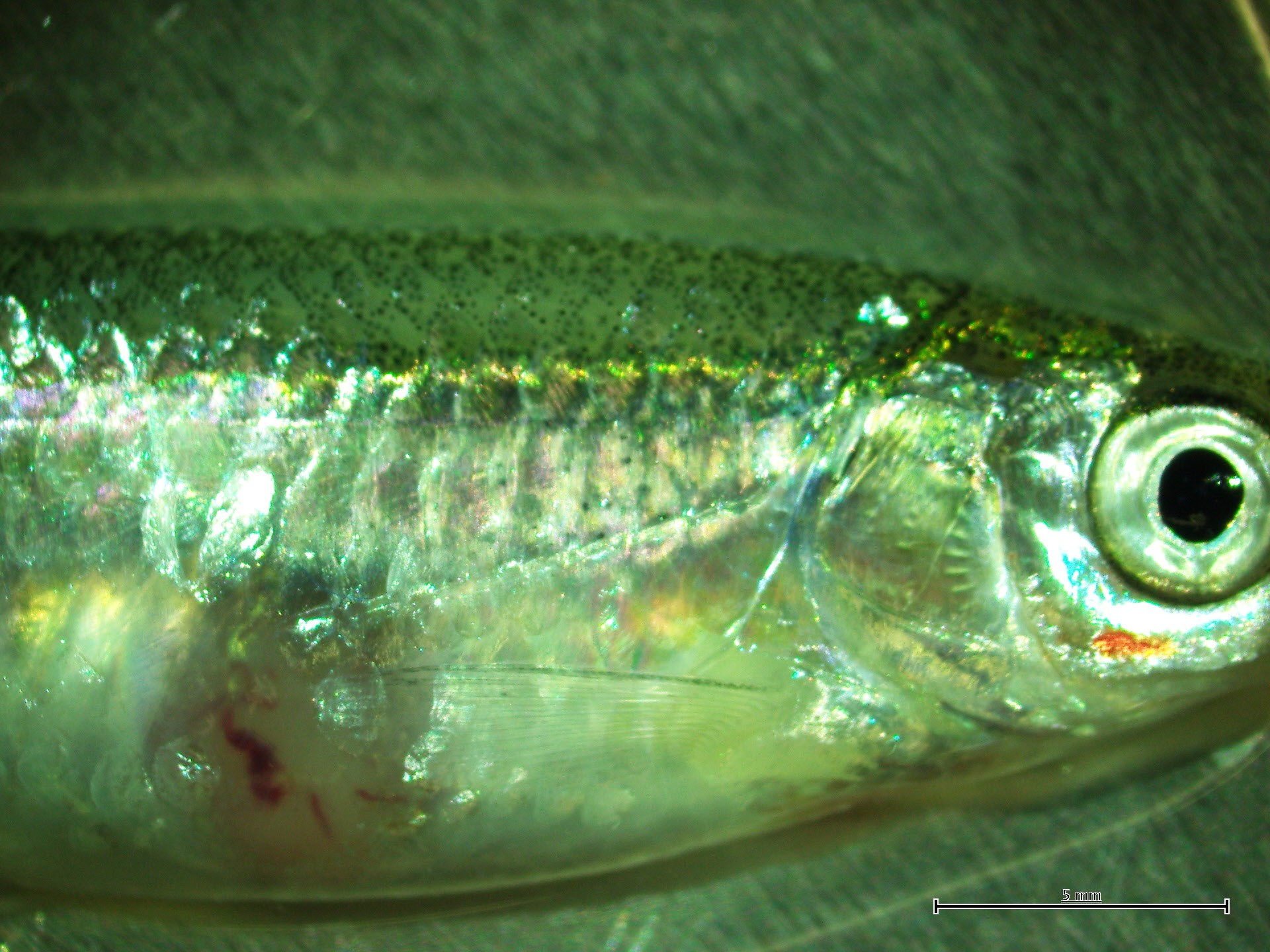

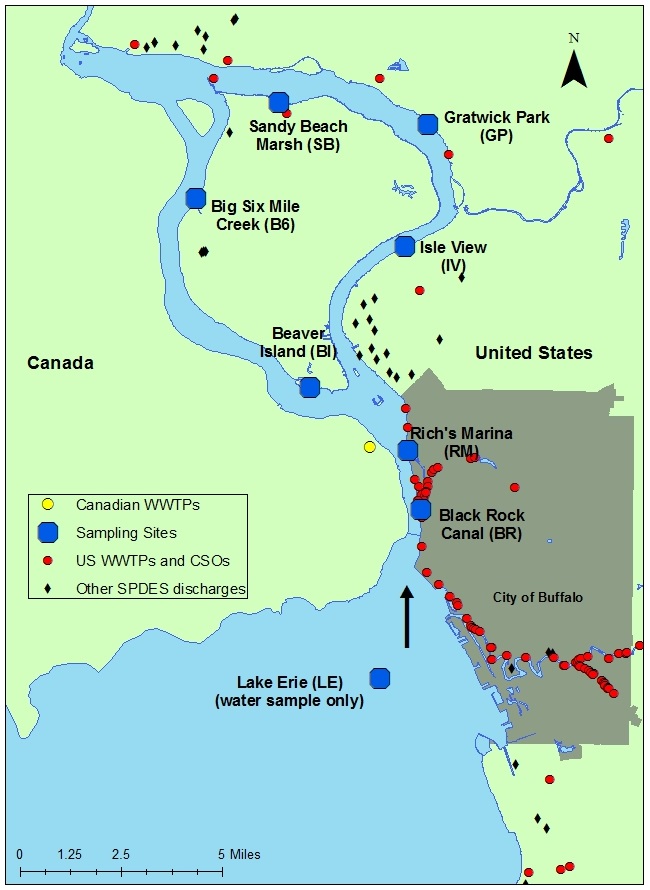

The objective of this thesis project was to determine whether or not wild emerald shiners exhibit immunological stress in response to sewage and fecal bacteria in the upper Niagara River, where there are heavy urbanization and waste water treatment plants that drain into the river. Emerald shiners rarely live more than three years, so their health status may reflect short-term exposure to water quality.

Emerald shiners and water samples were collected from seven sites in the upper Niagara and one site from eastern Lake Erie as reference for ambient E. coli levels. The fish were assessed for biological stress and tested for bacterial contamination in their livers.

Some frequently encountered factors contributing to poor health were: abnormal white blood cell values, hemorrhaging in body or eyes, high numbers of parasites, and mucous-covered gills. Approximately 35% of sampled emerald shiners had bacterial contamination in their livers. Despite the shiners’ sensitivity to the stressors in the river (e.g. pollution), E. coli levels in seven of the eight water sampling sites were generally within acceptable limits set by the EPA for recreational use, which may not be adequate to protect aquatic life. Evaluating immune stress due to sewage input into the river is a tool that provides insight into whether the Niagara River ecosystem is functionally adequate to preserve the health of aquatic organisms.

Large lesion, swollen abdomen and hemorrhaging below eye of an emerald shiner (left). Bacteria cultured from an emerald shiner (right), see the white colony in the red-blood media. This coliform is hemolytic, meaning that it degraded the surrounding red blood cells from the blood nutrient agar. Hemolytic bacteria are often pathogenic and harmful to their host.

Map of sampling sites with all nearshore waste water treatment plants (WWTP), combined sewer overflows (CSO) discharges, and other New York State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (SPDES) points, which are industrial point sources that release non-sewage effluent.

Map of sampling sites with all nearshore waste water treatment plants (WWTP), combined sewer overflows (CSO) discharges, and other New York State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (SPDES) points, which are industrial point sources that release non-sewage effluent.

The goal of this thesis project was to improve our understanding about early life history of emerald shiners in different habitats and determine the contribution of these fish to the diet of regional sportfish. We sampled community assemblages of larval and juvenile fishes throughout the Niagara River. In addition, stomach contents and stable isotopes analyses of sportfish were used to identify which prey fish they consume most often.

Larval fish were captured at fourteen sites throughout the upper Niagara River, ranging from natural marshes, island, and creek mouths, to more developed habitat sites such as marinas and seawalls. Juvenile emerald shiners were first captured in July, and continuously through August. It was found that they grew 1.5 mm in length and 31.5 mg in weight each week, and they were in the best condition during the warm water temperatures of August and September. Most larvae were found in areas where water flows formed gyres, suggesting that the spawned eggs and larvae may become entrapped in them. Juvenile fish communities were more diverse in the natural habitats as opposed to the developed sites, which lacked vegetation cover. Emerald shiner adults and juveniles were an extremely important prey species for sportfish (walleye and steelhead trout), comprising over half of their diet in the river.

Emerald shiners are a key forage species in the fish community assemblage of the upper Niagara River. The combined effects of juvenile habitat loss (marshes), invasive species, and degraded water quality require that this native forage fish becomes a priority for scientists and fishery managers to restore their habitat in order to maintain the ecological integrity of the aquatic food web in the Niagara River.

Photos in clockwise order: A larval fish emerald shiner, less than 15 mm in length. Adult emerald shiners recovered from the stomach of a walleye. Jake with a walleye captured at Broderick Park.

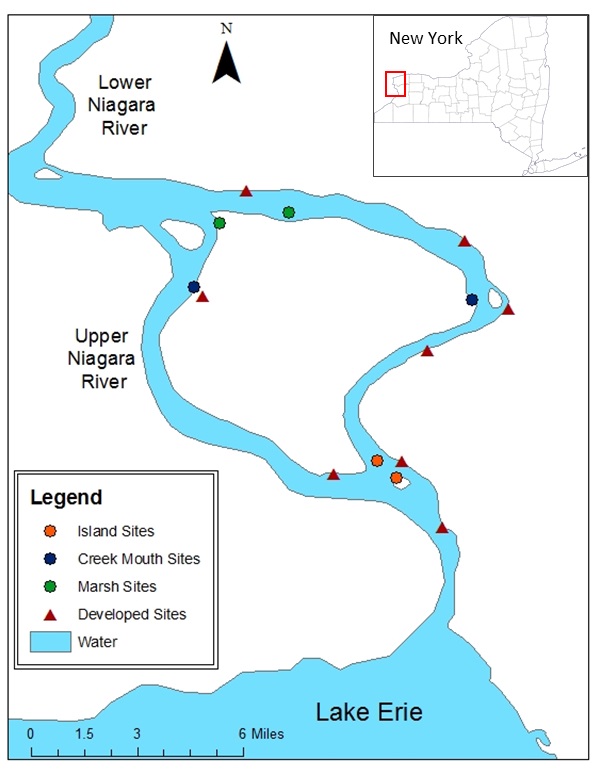

Map of sampling sites which distinguishes between naturalized and developed sites. Sites were seined for larval fish communities every other week.

Map of sampling sites which distinguishes between naturalized and developed sites. Sites were seined for larval fish communities every other week.

Some content on this page is saved in PDF format. To view these files, download Adobe Acrobat Reader free. If you are having trouble reading a document, request an accessible copy of the PDF or Word Document.